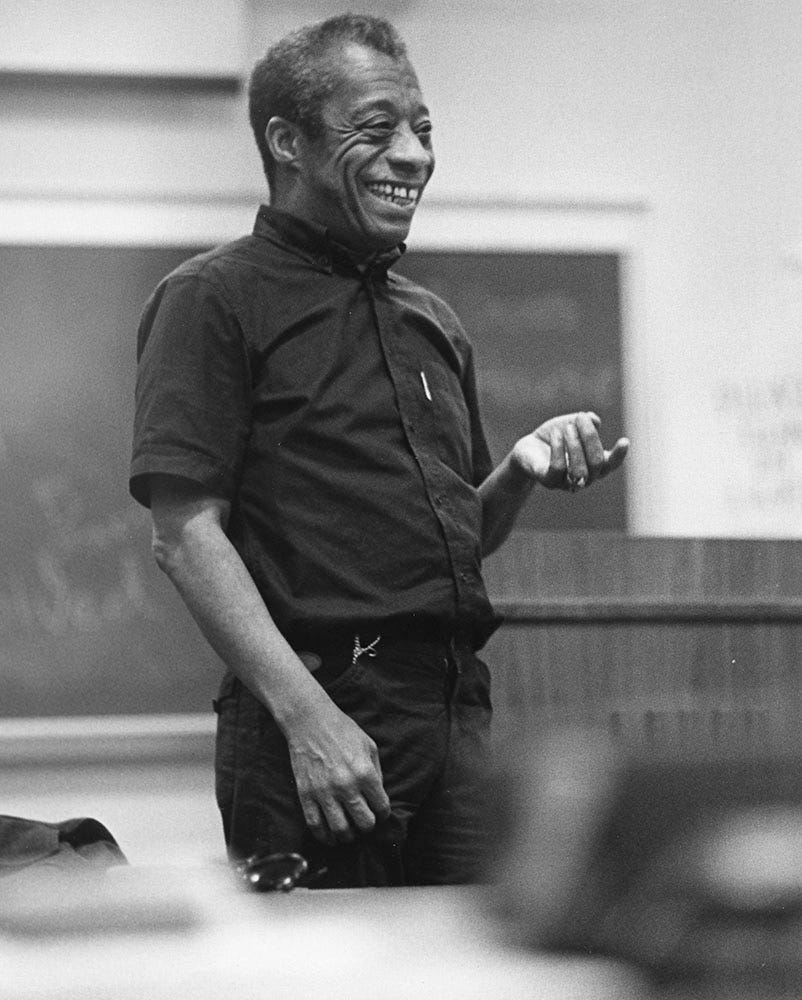

In fall of 1978 James Baldwin - novelist, essayist, and heralded literary artist - taught his first college course as writer-in-residence at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. In the first minute of his first class as a first-time college professor, Baldwin opened with a question:

“What shall we talk about?,” he asked the room.

After a bit of silence, a white student spoke. “Why does the white man hate the n******?”

Baldwin thought for a second, then said, “Why do you think the white man hates the ‘n*****’?”

And the students began to discuss the question.

Baldwin would later write in an essay titled “Dark Days,”

“In the ensuing discussion the children, very soon, did not need me at all, except as a vaguely benign adult presence. They began talking to one another, and they were not talking about race. They were talking of their desire to know one another, their need to know one another; each was trying to enter into the experience of the other. … They were trying to put themselves and their country together.”

The socratic elements of Baldwin’s teaching are immediately apparent: the posing of thought-provoking questions alongside a pursuit of productive discomfort. But where Plato’s dialogues put Socrates, the elder, in conversation with young men, Baldwin simply trusts the students to find their own way. The approach to teaching revealed in this story - Baldwin’s pedagogy, as Clint Smith might call it - involves radical trust in the students’ capacity to direct their own education.

Recent research in the field of education suggests that student-driven education can have a range of positive effects on learners. The Medical College of Wisconsin recently witnessed statistically significant increases in attendance and engagement with learner-centered curriculum units for fourth-year medical students, as compared to faculty-driven case-based sessions. In-depth interviews with college students in Iran revealed advantages of “negotiated” or “process” syllabi, where teachers and learners share decision-making around course organization, content, and learning outcomes. Additional studies from the previous decade have demonstrated positive learning outcomes when having students teach students, empowering students to design course syllabi, and simply asking students, “What do you want to learn right now?”

Gains of student-driven education can extend beyond curriculum goals, too. Research at a transnational university in China from 2022 shows that student participation in curriculum and syllabus design can increase “meta-cognitive awareness” of teaching strategies and tactics, power dynamics in the classroom, and the role of active self-reflection in transformative education. Lilly Padía recently recommended student-driven development of Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) as a part of broader disability justice goals of fostering agency and self-advocacy for disabled students. Qualitative assessment of college syllabi during COVID-19 emphasized the importance of learner-centered processes to achieving outcomes of accessibility, inclusivity, and equity in postsecondary education.

I have witnessed the potential of student-driven education firsthand as an instructor of a first-year seminar course affiliated with The Purpose Project, a program at the Kenan Institute for Ethics at Duke University committed to matters of character, purpose, and meaning in higher education. The course, “Education as Liberation,” invites students to take an active role in shaping their own education through collaborative prioritization of learning outcomes, development of curriculum units, and reflection on effective pedagogy.

On course evaluations, students describe the class as bewildering and unexpected. “I’ve never experienced anything like this before,” wrote one student. “The structure was completely contrary to my other classrooms,” wrote another. Opinions vary, too: “I didn’t like it, but I adjusted” on one side and “I wish every class was like this” on the other.

However they feel about the uniqueness of student-driven education, the students in my “Education as Liberation” course agree that it is utterly unique. It shouldn’t be, especially in light of the research, noted above, that supports its effectiveness in achieving both cognitive and meta-cognitive learning goals. The question is whether course instructors, department heads, and university administrators will exercise the personal and institutional agency necessary to push the pedagogical practice forward. In other words, will today’s teachers find the courage to trust our students to be as wise and discerning as we imagine ourselves to be?

This brings us back to James Baldwin standing in front of the room during his first college class. Of the student’s candid opening question, he wrote, “I was caught off guard. I simply had not had the courage to open the subject right away.” “I would have found a way to discuss what we refer to as interracial tension,” he added, but “The subject, I confess, frightened me, and it would never have occurred to me to throw it at them so nakedly.”

Baldwin admits to surprise, fear, and hesitation in the moment when he trusts the students to take charge of their own education. But, ever courageous, he receives these feelings as signs of achievement rather than failure in his role of instructor. The students were trying to put themselves and their country together, and even the great Baldwin knew that his best move was simply to get out of their way.

“I underestimated the children,” he recalled of that day, “I consider myself eternally in their debt.”

Emerging research confirms what Baldwin knew all along - that student-driven education practices have the potential to transform students, classrooms, and instructors. That transformation can begin as soon as the first minute of the first day of the semester.

So, class, what shall we talk about?

Extra Credit

Read “A Talk to Teachers,” Baldwin’s address to public school teachers in New York in 1963 at the Zinn Education Project.

Check out my book on Baldwin with Jamie McGhee - only $11! - You Mean It or You Don’t: James Baldwin’s Radical Challenge.