Why You Should Not Buy My Next Book (At Least Not Yet)

Notes on book prices, author royalties, and economy of academic publishing

I have a new book coming out in two weeks. I’m incredibly proud of the work—it’s been years in the making and is the result of deep listening, friendship, and intellectual collaboration. Writing the book stretched and challenged me in ways I’d never been stretched and challenged before, and its themes matter now more than ever.

I don’t want you to buy the book—at least not yet. Why?

Because the list price is $130. One hundred and thirty dollars.

Let’s talk about that sticker price, why you shouldn’t pay it, and if you’re interested in the book and its themes, what you can do instead.

Why Academic Books are So Expensive

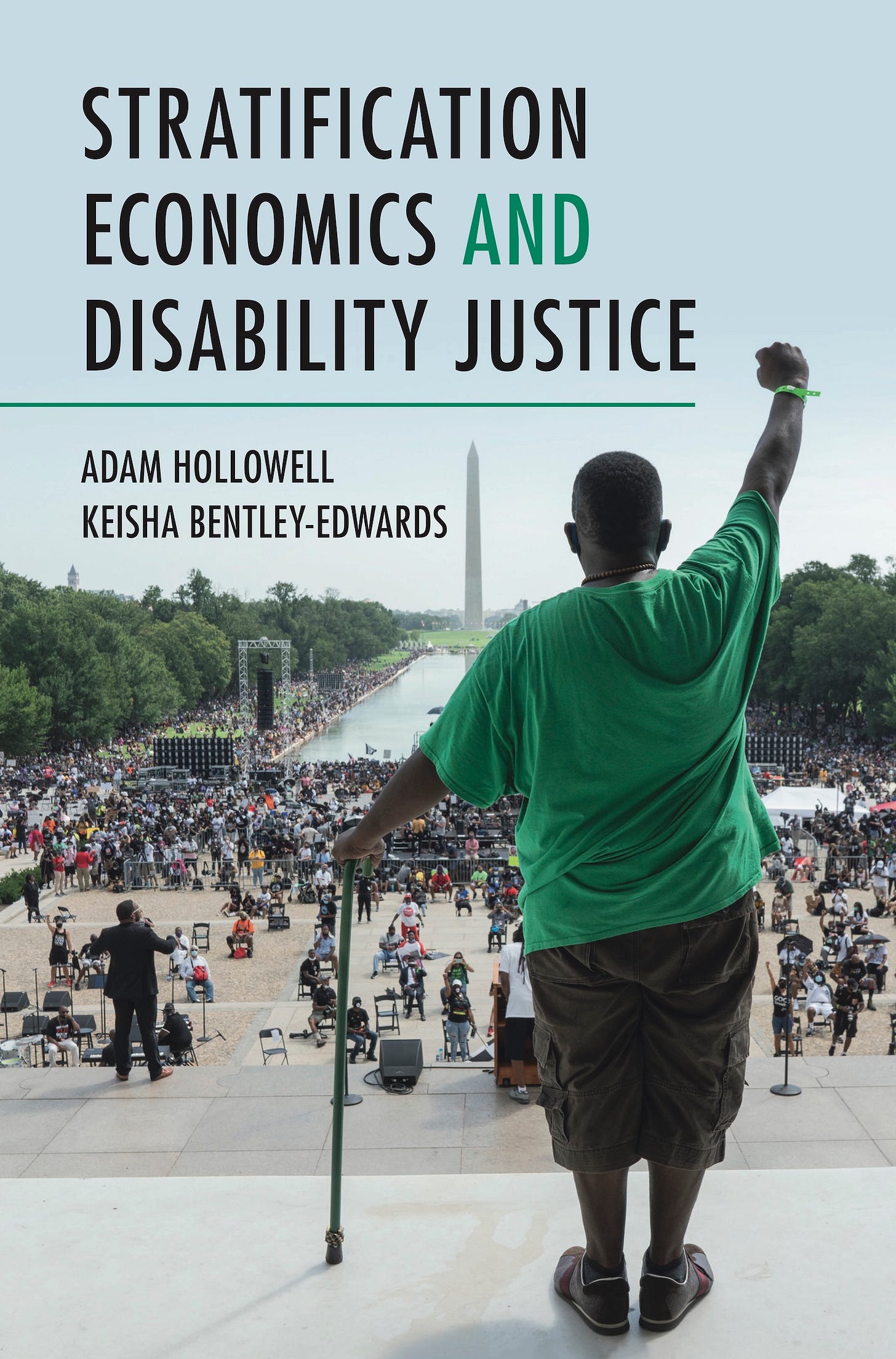

First, the basics. The book is called Stratification Economics and Disability Justice. I wrote it with my friend and Duke colleague Keisha Bentley-Edwards, an interdisciplinary researcher focused on how racism, gender, and culture influence health and education outcomes. It’s published by Cambridge University Press as a part of a series called Studies in Stratification Economics.

(If you’ve never heard of “stratification economics” or “disability justice,” just hold tight. My next newsletter will be about what those terms mean, why Keisha and I use them, and the disabled scholars and activists across the United States who inspired us to write this book.)

Cambridge University Press is what’s called an “academic publisher,” meaning their primary goal is to produce works of scholarship that contribute to the ever-growing body of human knowledge. Other publishers have other goals—for instance, “trade publishers” aim to make money, while smaller independent presses often have a more literary mission, etc.

Academic publishers sell predominantly to three audiences: researchers, who often buy books with university-funded research budgets, students, who are required to buy textbooks for their classes, and university libraries, who have budgets to maintain up-to-date holdings, which is a requirement of the university’s accreditation.

All three audiences are more or less required to buy academic books, though students are the only one of the three spending their own money to buy them. Yet all three audiences, even when added together, make for a fairly small market. Unless a book becomes an instant classic or a generationally-popular textbook, the publisher may only expect to sell a few hundred copies. If that.

Author and reporter Jane Friedman releases an annual guide to book publishing that’s so helpful I have it printed and tacked to a wall in my office. About academic publishers, Friedman says: “They tend to focus on selling through libraries and university systems” and “Pricing typically runs too high for bookstore placement.” Hardcovers in particular are priced with library budgets in mind.

In other words, when you combine required purchases, university resources, and small markets, you end up with very, very high prices.

You end up with a new hardcover book that costs $130.

The author’s making money though, right?

Not exactly. Not even close, actually.

While working on this post I re-read the contract I signed with Cambridge University Press. It turns out that I can’t tell you how much I’m going to make on Stratification Economics and Disability Justice. (It may or may not say “The Author shall not use Cambridge’s confidential information (including the terms of this Agreement …) for any purpose other than to perform the Author’s obligations …”)

But I can tell you about some industry averages.

Book sellers (Amazon, Barnes & Noble, your local independent bookstore, etc.) typically purchase a book from the publisher at a 40%-50% discount from the list price. So if the list price of a book is $20, the bookstore pays the publisher between $10-$12 for the book and can then (leaving out costs to keep this simple), sell the book for anywhere between $12.01 and $20 to make a profit.

The publisher brings in 50%-60% of the list price, but doesn’t mean that the publisher makes 50%-60% of the list price. Books are expensive to produce! Publishers have to pay to edit, design, manufacture, and market the book, then warehouse, distribute, and ship it. They also have to pay for professional staff in acquisitions, editorial, production, legal, accounting, management, etc.

What’s left after all of those expenses is called net revenue, or sometimes “margin,” and this number could be anywhere between 30%-40% of the list price depending on publishing costs. On a $20 book this would be between $6-$8.

That brings us to the author. What the author makes—“author’s royalties”—are typically between 5%-15% of net revenue. For a $20 book, if net revenue was $7, the author would receive between $.35 and $1.05 per copy sold. If there are two authors, that number gets split in half. Each author receives approximately $.53 cents. (For the curious, here’s a guide to royalties.)

Again, I can’t tell you how much I will make on Stratification Economics and Disability Justice. But I can tell you that, if we take the midpoint of all those industry average ranges I just ran through and applied them to a book with a list price of $130, the numbers would look like this:

List Price (100%): $130.00

Bookseller Cost (45%): $58.50

Publisher Revenue (55%): $71.50

Net Revenue (35%): $45.50

Author Royalties (10% of 35%): $4.55

Co-Author Royalties Split: $2.28

You read that right. $2.28 per copy.

What You Can Do Instead

This model doesn’t work for customers: $130 is too high. It doesn’t work for authors: $2.28 is too low. (That’s why Jane Friedmans says the value to authors is “Credibility and validation within the academic or literary community; help for tenure for professors.”)

What’s most troubling is the gatekeeping. The information in these books—remember that mission to contribute to the ever-growing body of human knowledge?—is restricted to elite institutions and well-funded researchers. It’s not Cambridge University Press’s fault. It’s just how the economic model works.

So what can you do instead, if you’re interested in the book and its themes?

First, keep reading From the Ethics Desk! I’ll be writing (free!) posts in the weeks ahead about the book and why its message matters.

Second, if you’re at a university, ask your library to order a copy. Academic libraries have budgets for exactly this purpose, and your access should be free. Just Google “request a purchase” + your university + library. You can see Duke’s version of the form here.

Third, our publisher has agreed to make chapter one, which lays out the theory of the case of the book, available for free for one month on Cambridge Core once the book is published. I don’t have the link yet, but once it’s available I’ll update the post to have it here.

Fourth, Keisha and I are looking for podcasts, blogs, and newsletters to join as guests! We’d love to talk/write about economics and disability justice on as many free-to-access forums as possible. Let us know if you have a favorite forum that would be a good fit!

And, finally, there’s this. A paperback version of the book should appear 12-18 months after the hardcover version, with a price of $29.99-$39.99.

That’s not cheap, but it’s a lot better than $130.

In this economy, we’ll take it.

Thanks for this post. I'm in law school right now, and I've had several casebooks run me $500!! And 80% of the material in those books (e.g., court decisions) is publicly available!! Feel terrible that the authors only see a small fraction of that.

I also think you're understating the publishers' margins. If you compare their net revenue to the price at which they sell to bookstores, the margins are upwards of 50%. For your example, if publisher revenue on a $130 book is $71.50, and they have a net revenue of $45.50, that means their profit (prior to paying author royalties) is ~63%!! Would be interested to see how that stacks up against trade publishers.

Hope you are well, Professor Hollowell!