Ten Years Later: Reflections on My First Book

Notes on learning from Paul Ramsey, leaving Christian Ethics, and owing my publisher $174.35.

Ten years ago this week, on January 26, 2015, I published my first book: Power and Purpose: Paul Ramsey and Contemporary Christian Political Theology. It was the culmination of my academic work in the field of Christian Ethics to that point, and I hoped it would bolster my candidacy for teaching jobs in seminaries and religious studies departments. A decade later, I’m thinking about the book, what I learned in the process of writing it, and how significantly my intellectual life and professional trajectory have changed in the decade since.

Let’s start at the beginning.

Learning from Paul Ramsey and Oliver O’Donovan

I first encountered Ramsey’s work in the first week of my PhD program at the University of Edinburgh. In our initial meeting my doctoral advisor, Oliver O’Donovan, handed me a list of 40 books, including several by Paul Ramsey. He said, as I remember it, “Read these and write something.”

I asked Professor O’Donovan where to start on the reading list, how much I should write, and when the assignment was due. His answer was, as I remember it, “Are you here to be a student or a scholar?”

His question implied that students complete assignments, while scholars structure their own intellectual work, generate their own projects, and decide for themselves how much (or little) to write. Later, standing in the hallway with the list of books in my hand, I understood that I was very good at being a student.

As a scholar, I had no clue. So I got to work.

Paul Ramsey (1913–1988), I learned, was a prominent Christian ethicist and professor at Princeton University, where he taught undergraduates for four decades. His writings shaped 20th century political theology and ethics, including just war theory, medical ethics, and the role of the church in modern life. (What’s political theology? It’s what the church says when it is talking about the state.)

Eventually I learned that Ramsey’s papers—collected letters, notes, manuscripts, and audio recordings from a lifetime of teaching and writing—were held at Duke. I decided to skip the unending darkness of a Scottish winter and spend a spring semester in sunny North Carolina. In Ramsey’s papers I found letters from a young doctoral student called Oliver O’Donovan who was, in his own way, learning the difference between a student and a scholar.

On Writing and Publishing (It’s 95% Revision)

Writing Power and Purpose took longer than I expected and, looking back, I’m glad it did.

I defended my doctoral dissertation in August of 2009. The “internal” examiner (from the University of Edinburgh) was David Fergusson and the “external” examiner (from Villanova University, now at Georgetown) was William Werpehowski. At the conclusion of the examination (I passed!), Professor Fergusson recommended that I break the dissertation into pieces and submit them as essays in peer-reviewed journals. After a few cycles of feedback, editing, and approval from journals, he reasoned, I would be in a stronger position to pitch a book on Ramsey.

So that’s what I did. Between 2010 and 2012, I revised, submitted, revised again, and published four peer-reviewed articles on Ramsey’s work. That process—going through multiple rounds of peer review by various academics, receiving tough criticism, and learning to rewrite entire sections from scratch—was crucial for my development as a writer.

When you’re an undergraduate, 95% of writing is the first draft and 5% is editing. Often you’re writing up against the assignment deadline in the middle of the night and, if you’re lucky, you meet the required page length just in time to give it a quick read-through before hitting submit.

In professional writing, 5% of writing is the first draft and 95% is editing. That was a difficult transition to make, as a writer, and a difficult lesson to learn, as a person, but I have found that it only gets truer over time. The slow, patient work of editing is everything.

By the end of 2012, I had a full book manuscript ready to submit. At the recommendation of a mentor, the first publisher I tried was Baylor University Press. The editor sent back an email the following day that ended with these lines:

“The very qualities that make this a fine thesis are the same qualities that make it an almost impossible book. Take comfort—not all great research makes its way into a book.”

I suppose the “great” was meant to be affirming, but I found “take comfort” to be particularly condescending, as if his evaluation was the final word in all of publishing about whether the manuscript was book-worthy. What’s more, I knew the manuscript I submitted wasn’t my doctoral thesis—it was the product of four additional years of rewriting, revising, and expanding that material. More than 60% of the book was entirely new.

After the sting of his response subsided, I went through the manuscript and deleted every footnote that wasn’t absolutely necessary. By the time I was done, the manuscript dropped from 90,000 words to 80,000 words.

10,000 words of unnecessary footnotes? That’s probably why it read like a thesis.

I sent the new manuscript to a few other presses, then later that year to Eerdmans. Jon Pott, the editor there, took a few months to reply but wrote with good news:

“If I am now too late, I would certainly understand and could only wish you well in an arrangement elsewhere, but we would very much like to publish the work.”

It turns out the great research was book-worthy.

Moving on from Christian Ethics

I thought the good news of publication would be the start of something for me in the field of Christian Ethics. Turns out, it was the end.

Power and Purpose will most likely be the last full-length book published on Paul Ramsey. It’s not because my book is that good—I didn’t set out to write the last book on him, anyway—but because that’s where we are. Ramsey’s influence has faded and very few instructors would even assign his work in a class on Christian Ethics. Very few instructors, especially at the undergraduate level, teach Christian Ethics at all.

I like to joke that two things pushed me out of Christian Ethics as a profession. The first is that I wasn’t very good at Christian Ethics. The second is that Christian Ethics doesn’t really exist anymore.

In the 1930s, every Duke undergraduate was required to take a course in Christian Ethics. That requires a lot of people who can teach it. Today, there will be perhaps 5 or 6 Religious Studies majors in a graduating class of 2,000+ students. I’m certainly not wishing for higher education to go back to the days of the 1930s, but there isn’t an open professorship in Christian Ethics within 500 miles of where I sit right now. Doctoral students at Duke Divinity School now add a second discipline to their studies in hopes of finding work in another part of higher education: “I’m studying Christian Ethics and environmentalism.” “I’m studying Christian Ethics and artificial intelligence.” That’s what I mean when I say Christian Ethics doesn’t really exist anymore.

As for me, I didn’t light the world of Christian Ethics on fire the way that Traci C. West, Jennifer Harvey, Willie James Jennings, or Sarah Azaransky did. And that’s okay. I slowly stopped applying for jobs in Christian Ethics and then quit entirely when I took a position at the Cook Center on Social Equity in 2018. I don’t go to Christian Ethics conferences or submit articles to academic journals in the field. It’s extremely rare that I meet someone who has read Paul Ramsey’s books, much less read my book on him. That’s okay, too.

The truth is, I studied for a PhD in theological ethics because I fell in love with theology and ethics and thought I would study them for the rest of my life. I was 25.

Then, at 31, I fell in love with James Baldwin’s writing and knew I would spend the rest of my life reading his work.

At 37, I fell in love with the radical claims of the disability justice movement. I’d get a PhD in disability studies if I could, but who has the time?

It turns out that my defining intellectual feature is curiosity, not commitment. As a person, I consider that a great gift. As someone pursuing a career in higher education, that has made things more complicated.

When I was 25, I didn’t realize that I’d discover a new passion every six years.

Now I’m 43, and who knows what’s next.

On Royalties and Including the “Edward”

How much did I make on Power and Purpose?

Less than $500—if I can remember that far back.

More interestingly, because booksellers have the right to return unsold books to the publisher, the publisher sometimes pays an author royalties for books that are eventually returned. As a result, for the past eight and a half years, I have received a royalties statement from Eerdmans every six months that shows a negative balance.

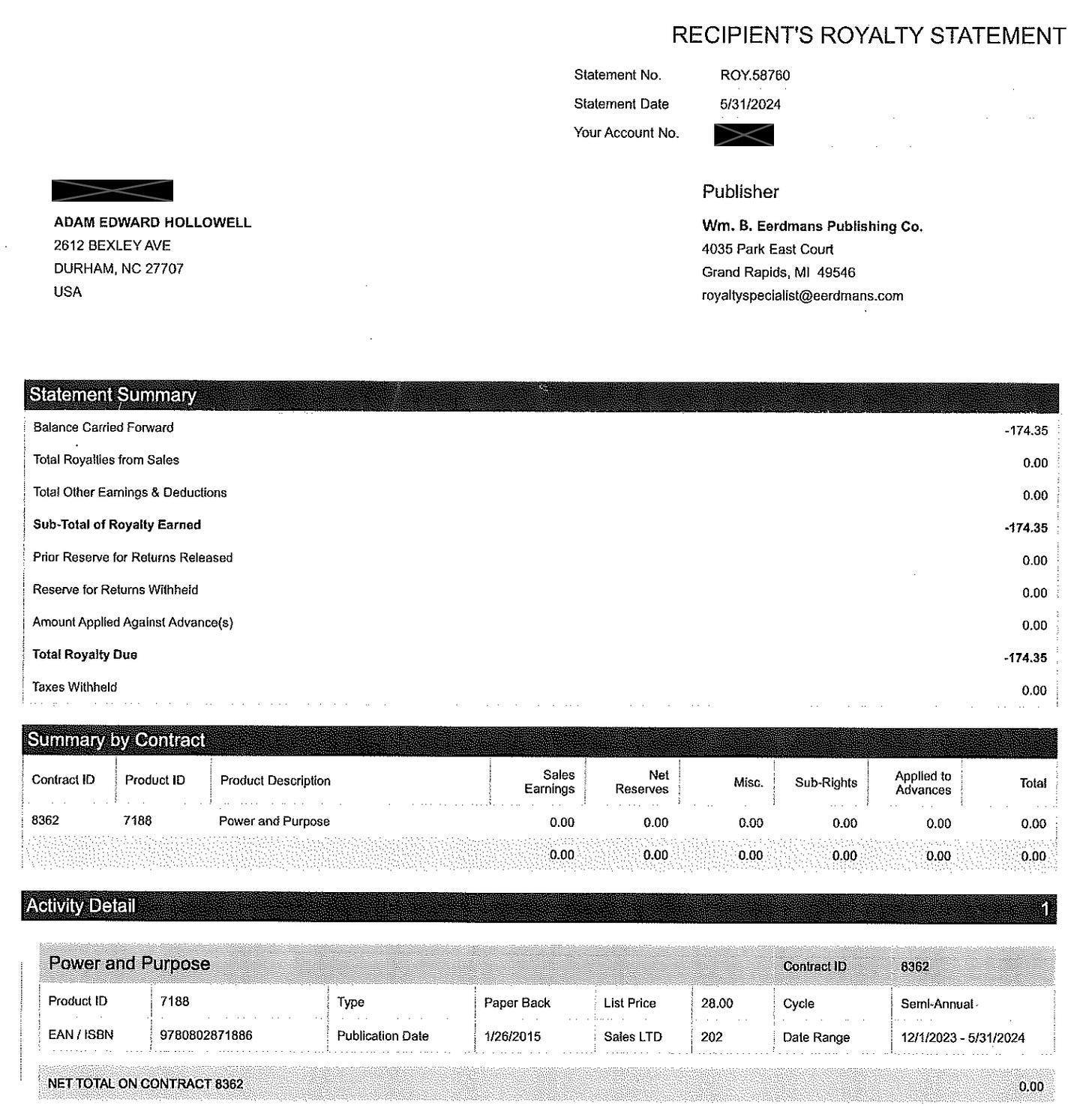

My most recent statement reads:

Balance carried forward: -$174.35

Total royalties from sales: $0.00

Other earnings and deductions: $0.00

Total royalty due: -$174.35

I don’t expect Eerdmans to come knocking for their $174.35. But it does make me laugh that instead of a check, I receive a twice-yearly reminder that Power and Purpose has debts to pay.

Why did I publish this as Adam Edward Hollowell?

I was always drawn to authors who published with their initials—H.R. Niebuhr being my favorite among the ethicists who did so. I thought that eventually I would publish as A.E. Hollowell as a tribute to my paternal grandfather, Albert Elvin Hollowell, who died a few years before the publication of Power and Purpose. I didn’t have enough of a name to publish with my initials right away, so I used my full name instead.

I gave up on the idea of publishing as A.E. Hollowell when I left Christian Ethics. Still, Power and Purpose is dedicated to my grandparents on both sides: Peggy, Vernon, Nita, and Al.

Final Reflections

I feel two things when I look back at Power and Purpose.

First, I’m proud of the work I did. It was a significant theological project that made a real contribution to scholarship on Paul Ramsey. The questions I wrestled with in that book—about power, war, and moral responsibility—still feel urgent today, even if the book grows less and less relevant to how we answer those questions.

Second, I’m grateful for what I learned. What I learned from Ramsey, Oliver O’Donovan, David Fergusson, and many other Christian ethicists, yes, but also what I learned about myself as a writer, editor, and scholar.

So here’s to ten years, Power and Purpose, and to whatever comes next.

Your changing curiosities (or maybe eras?) sure make it fun to follow your writing career and definitely make you a more interesting human. Proud of you! Can’t wait for the latest on disability justice!

You were a better at Christian Ethics than you imagine. Lol. And love that photo of you and Gerly. But I do appreciate what you’ve named about the discipline, and that you have the intellectual flexibility and simple curiosity to discover new interests every few years.